The positive impact of active learning took a giant leap forward in 2014 when Freeman et al. published “Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics”. Things to know about this important paper:

- There’s a LOT of heavy statistics and honestly, I find it quite difficult to read. I highly recommend this terrific blog post by Aatish Bhattia instead.

- The Freeman et al. paper focuses on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. That’s not because active learning isn’t effective in health science, education, social science, humanities,…but rather, because there is $$$ to study education in STEM education (because historically, STEM education has been so terrible!)

- The authors say, let’s stop proving active learning works – it does! – and let’s turn our attention to >why< it works. That’s ignited countless “second generation” research projects and articles digging into effective active learning.

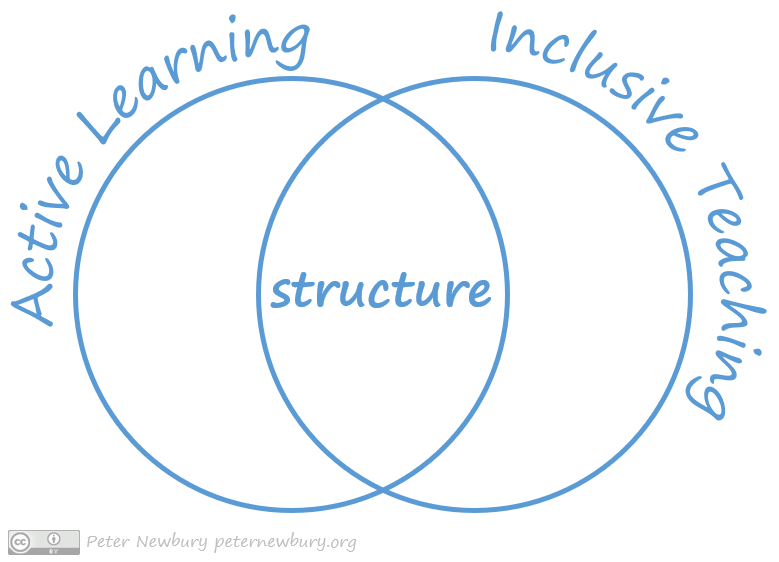

One of my favourite “second generation” papers is “Getting Under the Hood: How and for Whom Does Increasing Course Structure Work?” by Eddy & Hogan (2017). They show that classes with “highly structured” active learning increase the success of all students, with exaggerated impact on historically-disadvantaged groups. Their example of high structure is classes using the flipped learning model (students are guided on how to prepare for each class) and then peer instruction (polling using audience response tools) and/or worksheets in class.

And here’s where it all come together: providing structure and scaffolding and revealing the hidden curriculum about how to learn is at the heart of inclusive teaching. For a great overview of using structure to support inclusion, check out “How to make your teaching more inclusive” by Sathy & Hogan. (This is an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education and might require a subscription.) There was such overwhelming positive response to the Chronicle article, Sathy & Hogan turned it into an entire book, “Inclusive Teaching: Strategies for Promoting Equity in the College Classroom”.

The part of this story I like the most is this: after effective course design, I believe inclusive teaching practices are the most important component of a course. The research shows inclusive teaching isn’t warm and fuzzy / tokenistic / performative acts injected into your teaching. Instead, it’s careful, thoughtful, intentional design of the lesson and the course. And that’s something concrete we can all work on and practice.